Why Asia's cities need public spaces

Across Asia governments and city dwellers are taking a greater interest in the development and enhancement of the region's public spaces.

There is an ambitious infrastructure project underway in Wuhan, China — but it is not a mall, an airport, or an industrial development. Instead, it’s an open, green public space.

The project, called the Donghu Greenway, involves the rejuvenation of thirty-three square kilometers of the Donghu Lake area, the largest urban lake in China. Once it’s open to the public at the end of 2016, it will be car-free, have open parks, and include spaces for culture and education.

Far from bring the sole project of its kind, the Donghu Greenway is part of a program to create and promote urban public spaces in China amid a growing awareness of the need for these in the country’s rapidly urbanising cities. Furthermore, it’s a similar picture across Asia as governments and city dwellers take a greater interest in the development and enhancement of the region’s public spaces.

Fresh thinking in developing cities

The United Nations is committed to providing public space in the heart of the world’s developing cities. Its UN’s 2016-2030 Sustainable Development goals include making cities “provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities.”

This goal will have a significant impact in Asia, which currently holds 53 percent of the world’s urban population, and is home to sixteen of the world’s 28 megacities — large metropolitan areas with more than 10 million inhabitants.

For more newly developed Asian cities such as Cyberjaya and Taipei, local authorities are making progress. Dr Chua Yang Liang, JLL’s Head of Research for South East Asia and Singapore notes: “In emerging Asian cities, the policies can definitely have an impact in setting aside areas for public space. Now these cities are beginning to see the value of having more planned or organized integrated green park spaces. They see it as part of their urban solution,” says Chua.

Surabaya in Indonesia, for example, is one city where rapid growth has led to increasing land prices and a soaring property market. With space maximized inside homes, residents rely on public spaces. Joseph Lukito, Head of JLL’s Surabaya office, says: “The public spaces — including green areas and the city park — are very valuable in Surabaya, making the city look better, improving the environment and providing residents with open air places to socialize in.”

Among them is the Bungkul Park, a 15,000 square meter space that has an amphitheater, fountains, jogging paths, and a children’s playground. Like all of Surabaya’s city parks, it also provides free WiFi. A survey of Surabaya’s park visitors show that 80 percent of visitors enjoy these city parks once or twice a week, with the visitors coming from diverse socio-economic backgrounds.

Creating a modern heart

Older cities such as Manila and Mumbai face different challenges. Many have already been overdeveloped and face retrofitting more public spaces into their design. “That’s why it’s very hard for policies to have an impact, especially in older cities,” says Chua.

It’s far however, from impossible. Seoul, for example, transformed a congested highway into a landscaped walkway in the heart of the city which is now visited by more than 60,000 people a day.

Asia also has many privately owned public spaces (POPS), which are typically owned by developers but are accessible to the general population, including malls and commercial plazas.

For example, Singapore’s apartment blocks are known for their void decks — ground-level spaces that are kept empty to provide common space for residents. Since the 1970s, void decks have served as spaces for community events like weddings and funerals, playgrounds and art galleries.

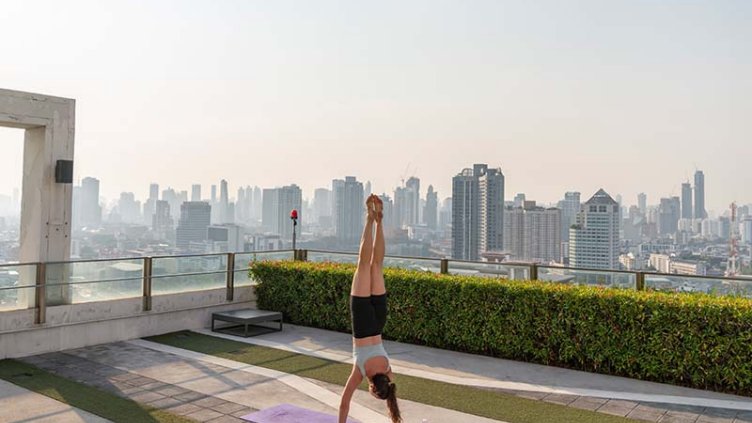

According to Chua, rooftop gardens also count as public space, and not just for the buildings under them. “These spaces enhance the value of the adjacent areas as well. So it’s not all hard, cold, concrete with utilities on the rooftops, but you get green spaces, you can have outdoor gardens within a building,” he says.

Investing for the future

As urbanization leads to denser cities and higher demand for available land, the pressure is on to create and maintain public spaces. There’s no one size fits all solution.

Some of Asia’s biggest cities are taking a communal approach to generate solutions by crowdsourcing ideas. Bangkok’s city government, for one, has launched the Inclusive Bangkok project, while Singapore’s Urban Redevelopment Authority’s runs an annual Ideas for Public Spaces competition and Malaysia has created is an annual arts and culture event known as Urbanscapes, that showcases Kuala Lumpur’s public spaces and creative communities.

And creating such spaces, particularly green spaces, are just the start: as a long-term commitment they require regular investment to keep them fit for purpose. “The challenges are in maintaining it and ensuring that the public spaces are kept clean,” says Chua.

For cities and the people who live within them, the benefits can outweigh the costs, improving the immediate environment, boosting quality of life and helping to create a thriving and prosperous society.